The true cause behind "net liquidity" working? I explore.

TLDR

· I posit “Net Liquidity” has correlated so well with equity levels since the pandemic started because it has effectively proxied a more root driver of equity valuations; the amount of zero-ish yielding bank deposits held by sophisticated folk who actively don’t want to hold them but in the aggregate cannot be rid of them (“hated deposits”).

· These “hated deposit” holders are motivated to pay up for other assets like equities, in turn immediately creating new bank deposit holders (whomever sold them the stock) who likely also don’t want to hold them: rinse and repeat.

· The deposits created by pandemic QE (B/S rise) became mostly of the “hated deposits” kind and there is some evidence in the FFIEC call report data to support this.

· The TGA works on “hated deposits” in a mirrored fashion to reserves in net liquidity temporarily absorbing them as it rises and recreating them as it falls. RRP also similar, offering a less hated alternative where the fed effectively absorbs some of those excess hated deposits,

· The pandemic QE created “hated deposits” added to the baseline level at the end of 2019 plausibly tracks the level of bank reserves/net liquidity over the last 2 years

· Like the S&P 500, “Hated Deposits” rose in 2019, unlike reserves/net liquidity which stayed mostly flat

Greetings!

“Net Liquidity” has puzzled me for a while now. I just couldn’t quite understand it. Not the equation that commonly defines it, that is simple enough:

· Total Fed Balance Sheet

· - TGA

· - RRP

· = Net Liquidity

But wait, isn’t that really just bank reserves when you further remove currency (which is mostly constant), assume RRP includes the foreign RRP (not sure why it doesnt), and remove the 200 billion ish of “other” Fed liabilities which also remain fairly steady over time? Seems that way to me and in this analysis/theory discussion we will use “net liquidity” as a fancy name for bank reserves. But whatever ones precise definition, the really fancy thing is how well it correlated to the S&P 500 level the past few years.

But why? Why would the level of reserves (+ some pseudo-constants) at commercial banks correlate so well with equity valuations? There are clearly well more than enough of them to settle the system each day (while keeping banks within their intraday liquidity constraints), why would additional or fewer but still ample reserves in the banking system matter to equities? I had no conceptual idea and couldn’t come up with no want for trying.

Then I stumbled on Andy Constan’s Liquidity 101 thread

Specifically later in his thread,

“Let's throw Fed purchases into the mix. The fed buys the issuance and the market need not adjust. The spending is distributed to savers and spenders and over time ends in savings which needs investments and there is no new supply”

It struck me that the savings he was referring to were bank deposits (until and unless they buy better yielding investments). Ding Ding It’s the deposits stupid! (me being stupid, not you) and maybe the reserves really don’t matter like I conceptually think they shouldn’t. That thought prompted me to remember something Dr. John Hussman posted which I did not fully grok when he posted it in November but now made complete sense.

“Monetary hot potatoes”, was a great way to put it, though im a touch partial to “hated deposits” which I use to describe the same idea. Anyways, if we assume that these “hated deposits” push up other assets like equities, it stood to reason that maybe “net liquidity” worked so well in recent times because it acted as a proxy measure for the level of these hated deposits. So I did a little research and analysis to see if I could prove that.

Unfortunately, I cant conclusively do it, but there is some circumstantial evidence in favor of it, making it at least plausible to me. That, combined with “net liquidity” working because it proxied for something that lifted equity valuations through a mechanism I could understand and describe has me convinced enough its on the right path. A much more comfortable place to be than just being baffled on why it worked. Whether or not you too find the evidence Ill go through as convincing I leave to you, but either way I hope you find the research and analysis interesting and the “hated deposit” point of view on our money system a valuable perspective to consider.

Hated Bank Deposits

Per the FFIEC call reports (available at https://cdr.ffiec.gov/public/ManageFacsimiles.aspx#), on 12/31/2019 there were ~13.2T dollars in deposit accounts in domestic offices of US banks. Two years later, on 12/31/2021 that number grows ~5T to 18.2T.

Most of that increase was due to the Feds Covid QE which also increased the size of the Feds balance sheet by about 4.6T over the same time frame. Not all though, ~2.4T (~2T deposits were “trapped” in the RRP on 12/31/2021) of deposit growth must have been due to banks making loans that increased deposits and other organic ways deposits grow. But most of those deposits came to be as a result of the Fed’s mass buying of UST and MBS (FED buys MBS from non-bank, credits the non-banks bank with freshly minted reserves which the bank then balances with new deposits for that non-bank)

Were all those 13.2T in deposits on 12/31/2019 hated? Certainly not, many deposits are not hated. Why? Well for one, bank deposits are the only effective way to pay for most stuff these days. Sure there’s currency, but not practically for most purchases anymore. So if we want to buy stuff we need to have some bank deposits to pay for it. On the flip side, if we want to sell stuff/our labor, we are almost certainly going to be paid in bank deposits. This goes for people and institutions alike, both need some amount of bank deposits handy to settle transactions. Those bank deposits are not hated, regardless of yield.

What about the deposits in excess of what is needed operationally for day to day life? The degree of hate for these deposits depends on a few things, the most important, I think, is who holds them and how sophisticated financially those folks are.

For retail folks (in the aggregate unsophisticated), I posit that these bank deposits aren’t really hated either (sure some, but mostly not), generally because the opportunity cost of holding them versus other assets just isn’t really thought about much and while maybe they should be hated, they aren’t and just sit there. You can see this expected retail deposit stickiness expressed in the Basel III liquidity rules that require banks to only invest 5% of retail deposits into HQLA to comfortably cover expected outflow.

Institutions on the other hand are more sophisticated and more likely to care about opportunity cost of holding bank deposits, particularly those in excess of their operational liquidity needs. Its these institutions that are more likely to inherently hate the deposit. You see this also echoed in the Basel III rules as banks must invest 25% for corporate operating deposits in HQLA, 45% for corporate non-operating deposits and a full 100% for non-bank financial corporate non-operating deposits.

Of course, there are other factors, like the perceived attractiveness of alternative assets, desire for immediate liquidity because of a developing global pandemic etc, that affect whether bank deposits are actually hated enough to be parted with, It stands to reason though that a larger pool of bank deposits held by those with a higher propensity to hate them will correlate to larger pool of actually hated bank deposits.

The Cycle of Deposit Hatred – Why “Hated Deposits” push up on other assets

Ok, a holder of hated bank deposits should have an easy solution to get rid of them right? Just buy an asset you prefer. Sure that works, but you have to find someone else to sell you that asset and if they hate bank deposits like you, you are more likely to have to pay their ask, and what then? Well now that former seller holds those bank deposits, and the delight they feel because they got paid their ask, is matched by a dislike of the bank deposits they now hold. So then they seek out an asset to buy, rinse and repeat, more often then not buying at the ask and pushing up the price of non-deposit assets

There are however, two notable off ramps to this cycle of deposit hatred. One, is when the Treasury is the seller of the asset (net new treasury or perhaps your continued good standing with the govt. paid for with remitted taxes). In that case, the hated deposits disappear for a while into the TGA but that disappearance is only temporary until the govt spends those funds creating those bank deposits anew, some of which again will likely become hated. Two, (and realize I am simplifying MMFs here a tad to stay on point) if the asset purchased was a MMF share that will take that deposit and convert it into a Fed RRP. Those “hated deposits” go away “indefinitely” or rather, for as long as the new MMF share owner does not redeem the MMF share (and no other safe collateral owning entity decides it needs/loves deposits enough now to outbid the Fed for it, in which case it would by definition not be hated).

The Pool of Hated Deposits prior to Covid

Now that we have a conceptual framework for which deposits are more likely to be hated and an understandable mechanism by which the hated deposits push on asset prices, lets try to quantify that pool.

Bank deposits on 12/31/2019 broke down as:

- 4.7T Retail

- 5.1T Institutional

- 2.5T Time Deposits (doesn’t matter if they are hated they are locked in for some period)

- .9T Govts and other banks (not folks to hate and speculate)

(The detailed methodology in how I extracted these numbers from the FFIEC call reports is included in Appendix 2 at the end of this article)

Our pool of hated deposits on 12/31/2019 is some portion of that 5.1T. The FFIEC call reports break this number down to 1.6T in transactional accounts and 3.5T in non-transactional accounts. But the lines between the transactional/non-transactional classifications in the call reports are blurry with respect to what would correspond to operating versus non-operating deposits. Using the basel risk framework would be considerably more precise but unfortunately bank reporting of deposits per that classification is done via the FR 2052a reports (https://www.newyorkfed.org/banking/reportingforms/FR_2052a.html) which are not public. So we cant tell precisely what of the 5.1T is truly operating vs. not. No worries, it’s a start. Going with the data we have we will just use the total level of institutional deposits less some amount of true operating deposits, and the increase of that total level as a proxy. Not perfect, but good enough for some supportive circumstantial evidence.

Enter Covid

Then Covid strikes, lockdowns happen, economic activity collapses etc. Ironically, almost overnight, whatever “hated deposits” there were in the banking system became very very loved as the Dash for Cash ensued and asset holders did their darndest to trade those assets for deposits. I think this is an important caution to remember, “excess” liquidity is excess against a level of demand for liquidity which can and did change dramatically and very quickly. So the Fed of course quickly stepped in to satisfy that liquidity demand buying trillions of those assets (UST and MBS) in exchange for reserves at the previous asset owners bank, which in turn balanced those reserves with deposits. 4.6T by 12/31/2021. But how many of them ended up held by likely to hate them institutions?

Turns out it looks like most of them…

Bank deposits on 12/31/2021 broke down as:

- 6.5T Retail

- 8.3T Institutional

- 2.2T Time Deposits (doesn’t matter if they are hated they are locked in for some period)

- 1.2T Govts and other banks (not folks to hate and speculate)

But now we are almost 2 years past the pandemic start and the fear that made liquidity so loved during the dash for cash is long gone, but the system is still left with a ton of new deposits: 1.8T in Retail and a whopping 3.2T in Institutional accounts.

Could some of that 3.2T in institutional deposit growth be needed for increased operational liquidity (thus unhated deposits) in a world where inflation was proving anything but transitory? Probably a little, but most of it likely went to “hated deposits”. (the Fed was buying UST and MBS after all to indirectly create those deposits) And the increased institutional deposits that went to operational liquidity were probably more than made up for by the normally deposit non-hating retail crowd who started showing distinct signs up deposit hatred (bored ape yacht club anyone?)

So what are you really saying John? Well if you start from some baseline level of “Hated Deposits”

that existed prior to Covid, some subset of the 5.1T institutional deposits on 12/31/19, say 1T (why 1T? knowing no better, I assume that in normal times institutional non-operating deposits have a tendency to reduce as sophisticated operators work to slough them off on less yield sensitive holders. But say its actually 4T, well then the numbers better match to traditional net liquidity instead of reserves so not sure the offset matters so much) of them, and then assume that most of the increase in institutional deposits from the QE cannon went to the pool of “hated” deposits, then you start to get a fairly decent correlation with Bank Reserves, which suggest to me that the idea that “Net Liquidity” worked because it proxied the rise in “hated bank deposits” is very plausible.

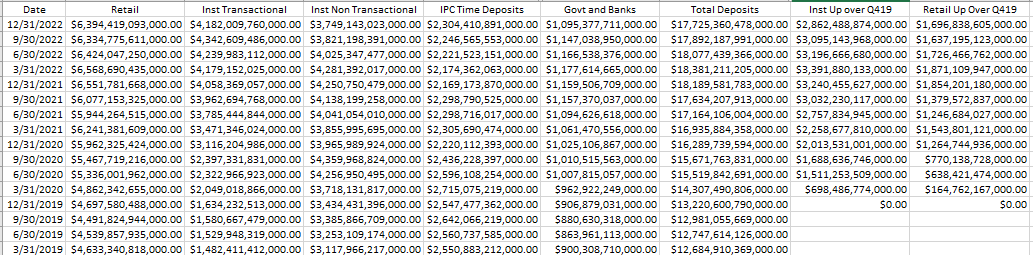

The table below lays out for each call report date, the numbers including the increase in institutional deposits from 12/31/2019 in the second column and the “net liquidity”/bank reserves level (pulled from the corresponding h.4.1’s and triangulated a little between the straddling weeks to account for the fact that many of these call report dates don’t line up with Wednesdays) in the third column. Values in millions.

Would I go to court with this evidence. No, not good enough for that. Would I much rather quantify “hated bank deposits” using Basel prudential liquidity classifications ? Yes if I had that data. But I don’t.

That said, for me at least, when paired with the benefit that higher levels of “hated bank deposits” correlate with higher levels of equity valuation in a way that makes conceptual sense (particularly versus reserves which I cant really conceive the correlation at all), its convincing enough

Plus, it helps explain “net liquidity’s” problematic 2019.

What about 2019?

One of the criticisms of the “net liquidity” model was that it did not correlate well prior to the pandemic.

How does “Hated Bank Deposits” fare? Much better it turns out.

3/31/2019 Bank Deposit breakdown

- 4.6T Retail

- 4.6T Institutional

- 2.5T Time Deposits (doesn’t matter if they are hated they are locked in for a bit)

- 0.9T Govts and other banks (not folks to hate and speculate)

12/31/2019 Bank Deposit breakdown

- 4.7T Retail

- 5.1T Institutional

- 2.5T Time Deposits (doesn’t matter if they are hated they are locked in for a bit)

- 0.9T Govts and other banks (not folks to hate and speculate)

Institutional deposits up 10% over that time frame (why such a big increase vs, retail? Dunno, something I intend to look into). S&P up by a similar amount over the time frame. While “net liquidity”/reserves stayed flat. Smoking gun? Maybe not, but definitely supportive of the general thesis.

Wrapping things up, this post is definitely much more on the speculative side vs. my posts on QT or even my post projecting the TGA level last month, and you should treat it as such. Personally though, I think Im on to something and feel better able to process whether and why the “net liquidity” correlation to equities levels is likely to continue. Regardless of whether you agree, hopefully you got some insight by reading it as well. By the way thanks for that. I genuinely appreciate your time and interest.

Best,

John

Appendix 1 Raw Data from the FFIEC call reports back to 3/31/2019

Appendix 2 How to extract the deposit amounts from the FFIEC call reports

FFIEC bank call report data is available here (https://cdr.ffiec.gov/Public/PWS/DownloadBulkData.aspx) I imported the call report data for all the banks for each of the quarterly dates from Q1 2019 through Q4 2022 into a local database . The relevant part of the call reports for this analysis is Schedule RC-E Part I - Deposits in Domestic Offices(Form Type - 031).

Retail Deposits are calculated by aggregating across all banks the sum of:

- 6a. Total deposits in those noninterest-bearing transaction account deposit products intended primarily for individuals for personal, household, or family use.

- 6b. Total deposits in those interest-bearing transaction account deposit products intended primarily for individuals for personal, household, or family use.

- 7a1. Total deposits in those MMDA deposit products intended primarily for individuals for personal, household, or family use.

- 7b1. Total deposits in those other savings deposit account deposit products intended primarily for individuals for personal, household, or family use.

Institutional Deposits are calculated by aggregating across all banks the sum of:

- 7a2. Deposits in all other MMDAs of individuals, partnerships, and corporations

- 7b2. Deposits in all other savings deposit accounts of individuals, partnerships, and corporations

- The total Transaction Account Deposits of Individuals, partnerships, and corporations found in Column A 1 from the main summary table less those attributable to retail (6a and 6b above)

Time Deposits are calculated as the total Non-Transaction Account Deposits of Individuals, partnerships, and corporations found in Column C 1 from the main summary table less the total amounts in 7a1, 7a2, 7b1, and 7b2

Govt. and other banks Deposits are calculated by subtracting the Total of all Transaction and Non-Transaction accounts found in A7 and C7 from the summary table less the amounts attributable to Individuals, partnerships, and corporations found in A1 and C1

An example of the SQL I use to extract the values is below. The column names like RCONP756 refer to the field tags in the call report.

select (sum(cast(RCONP756 as bigint)) + sum(cast(RCONP753 as bigint)) + sum(cast(RCONP754 as bigint))) * 1000 as RetailTransactionalMMDA,

sum(cast(RCONP758 as bigint)) * 1000 as RetailOther,

(sum(cast(RCONB549 as bigint)) - (sum(cast(RCONP753 as bigint)) + sum(cast(RCONP754 as bigint)))) * 1000 as InstitutionalTransactional,

(sum(cast(RCONP757 as bigint)) + sum(cast(RCONP759 as bigint))) * 1000 as InstitutionalNonTransactional,

(sum(cast(RCONB550 as bigint)) - (sum(cast(RCONP756 as bigint)) + sum(cast(RCONP757 as bigint)) + sum(cast(RCONP758 as bigint)) + sum(cast(RCONP759 as bigint)))) * 1000 as IPCNonTransactionalTimeDespoits,

(sum(cast(RCON2215 as bigint)) - sum(cast(RCONB549 as bigint))) * 1000 as OtherActorsTransactional,

(sum(cast(RCON2385 as bigint)) - sum(cast(RCONB550 as bigint))) * 1000 as OtherActorsNonTransactional

from [FFIEC CDR Call Schedule RCEI 12312021]

where ["idrssd"] != ''

Brilliant. Thank you for this. This is a great extension of Hussman’s zero-interest hot potato concept.

This is fantastic. Thanks John!