Greetings!

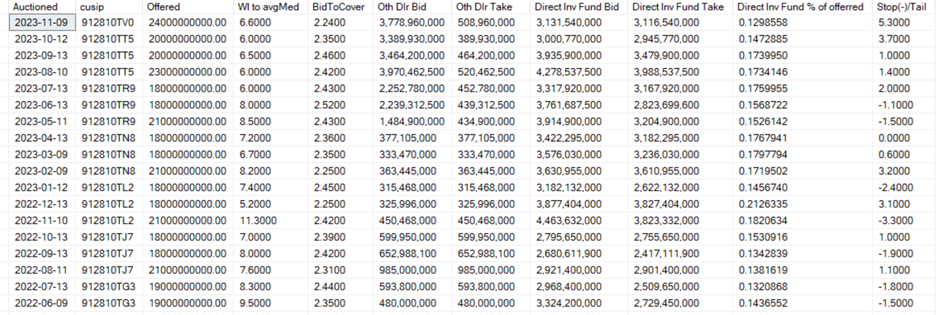

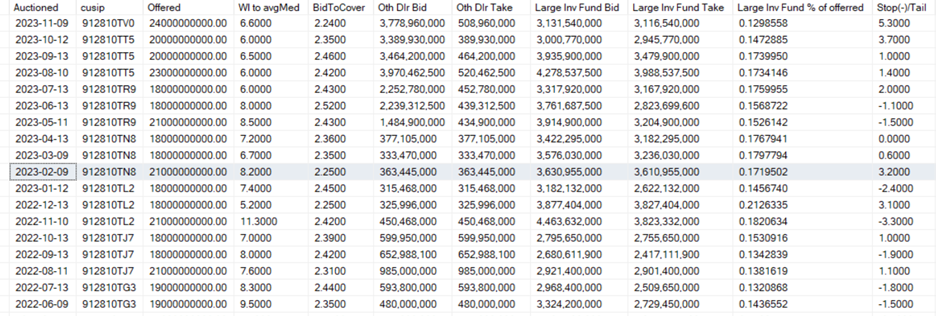

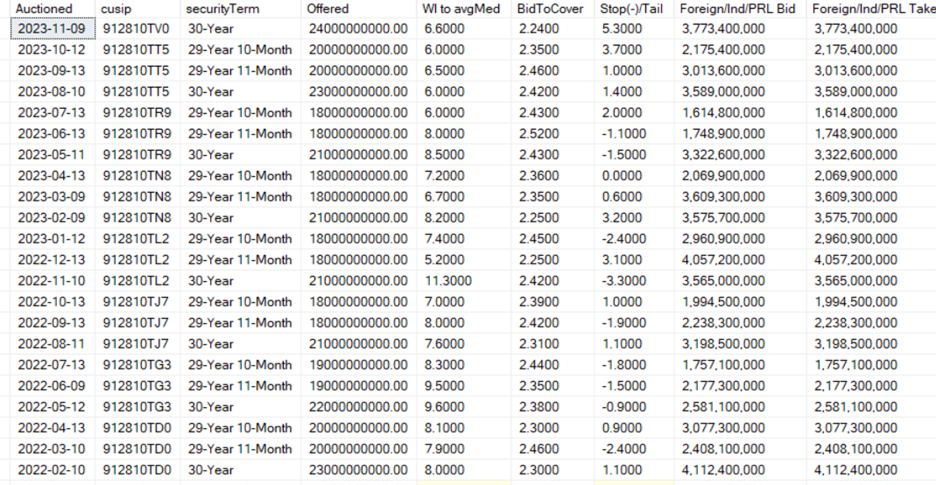

A few weeks ago there was a “catastrophic” auction of the 30 year bond. It was so “catastrophic” that the absolute chumps who bought in the When Issued market moments before the auction at a yield level of 4.716 were then immediately down 5.3 bp of yield levels when the auction printed t 4.769. Of course those same chumps are now up like 31bp of yield levels maybe it wasn’t so catastrophic after all for those last second before the auction WI buyers. Sure it was a little more expensive for Treasury than the WI market indicated it would be, and yeah the primary dealers may have had a bit more inventory than usual to sell off post auction but was it really catastrophic? I dunno. I think folks are a little quick and extreme with the superlatives regarding individual treasury auctions. That said, the auction did get close to touching the backstop bid required to be made from the primary dealers. Closer then most folks understand. Sure the auctions 2.24 bid-to-cover was ugly but it’s a whole lot prettier than the real bid-to-cover of the auction which was more like 2.11. Yep at least 3b in in direct bidder bid was not reflective of real demand (Primary Dealer mandatory backstop bid really isn’t either, but folks already factor that in). Moreover, overstated bid-to-covers isn’t limited to the 30-yr tenor. Its present in every treasury auction and its something folks should be aware of. I will, of course, explain.

Anyways, as someone who is keenly interested in outlier events and the mechanics behind those outlier events, the 11/9 30yr auction with its absolutely outlier 5.3bp tail inspired me to temporarily shelve my TGA projection efforts and super deep dive into the details of treasury auctions with this dispatch as the initial result of that research. Oh God John, is this gonna be yet another explainer on how treasury auctions work with the usual descriptions of bid-to-cover, stop/tail, and percentage take of primary dealers, direct and indirect bidders? Weve seen like 5 in the past three weeks (even doomer you tube bros are getting in on that act). Well part of it will be, there is a certain foundation of knowledge that’s required to understand where my analysis ends up. Ultimately though, what I am trying to do with this post is parse the available public data on the auction to determine in as much detail as I can, the folks who are bidding, in what amounts, and where on the spectrum of bids that Treasury receives, those bidders are placing their bids. When you do a detailed analysis on all the publicly available data on the auction, making some reasonable assumptions along the way you paint a pretty detailed and insightful picture of what that detailed bid profile looked like. So while this piece starts as a basic explainer on treasury auctions and how to read the competitive auction results using the 11/9 30 yr auction as a detailed example, it ends up in a place I think even grizzled bond vets will find interesting.

Since we gotta start somewhere…

What was Bid vs. What Treasury Offered (The Bid-To-Cover)

Treasury auctions are “Dutch” auctions. This generally means that Treasury is going to auction off a specific amount of Treasury securities, in the case of the 11/9 30 yr auction $24 billion worth. Unlike an ebay auction for a rare pokemon card though, bidders are not bidding on a single item/the full 24 billion allotment (in fact Treasury rules prevent them from winning more than 35% of the offered amount). Rather, each bidder bids for some piece of the offered amount at some price and the Treasury accepts the $24 billion highest bids. However, nearly all of the bidders don’t actually pay what they bid, but instead they pay only the price of the lowest bid. Everyone pays the same price. Of note though, bidders don’t bid a price in dollars per $100 of par bond value but rather in yield. So bidders may bid 4.705 for a bond or 4.724 (yield levels are in .001 increments) and if their bid is accepted they will pay the price equivalent of the highest yield (lowest price) bid that was accepted.

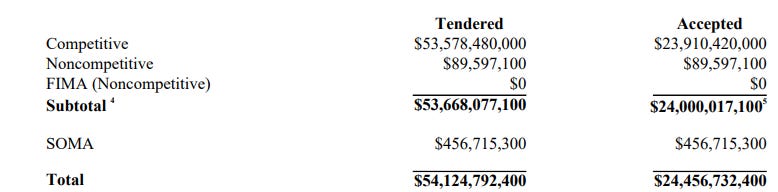

For the 11/9 auction, Treasury auctioned $24 billion worth of 30 year bonds. The public, in total, placed ~$53.7 billion worth of bids for those $24 billion worth of Treasuries. Put differently, the public was willing (or required) to bid some amount for $53.7 billion worth of treasuries. If Treasury had offered $53.7 billion instead of $24 billion the auction would not have “failed” and the auction price that everyone would have paid/ would have been the lowest bid out of the $53.7 billion worth of bids.

This brings us to our first common metric, the bid-to-cover, which is simply the ratio of bids made to the amount offered. So for us, that ratio is $53,668,077,100/$24,000,017,100 = 2.24. Intuitively a higher bid to cover indicates a “stronger” auction since it literally (given a fixed offering amount) means more bids for that offered amount, which sorta means more demand and probably means a higher auction price (lower auction high yield) since more bids cant possibly move the auction price down (raise the auction yield). But there is something very important to keep in mind, its not just the volume of bids that matter, it’s also the prices of those bids. So for our 30 year auction, if there was another 10b in bids, but all 10b of those extra bids were super low ball bids (high yield) then it would have a dramatic effect on the bid to cover raising it to 2.65 (one of the highest for a 30 yr auction in the last 10 years) but have absolutely no impact on where the auction ultimately priced. So when I say “sorta means more demand” what I mean is, low ball bids are technically demand, but they are a different sort of demand than high ball bids. Generally more bids in total probably means more high ball bids as well but it doesn’t have to and that’s important to keep in mind.

Before we move on to where the bids in our 30 year auction actually came in at and who made them, we need to dispense with two more concepts.

First, competitive vs. non-competitive. Non-competitive bids are bids where the bidder says, “I will pay whatever the auction prices at to guarantee I get the amount I bid for, think of it as sort of a “Buy it now” but for a specific amount of the auction but at a price that the market will determine at auction. It is a very small portion of the total auction and has the practical effect of reducing the amount being competitively bid on. In our case it reduces the 24b being competitively bid on to about 23.91b. Not literally nothing, but very small potatoes vs the competitive bid that actually determines the auction price/yield.

Second, SOMA. The SOMA take relates to treasury rollover of maturing securities which is influenced by QT/Fed balance sheet reduction along with the Feds policy on Treasury rollover. But, it has ZERO effect on the auction itself and where it prices. It is purely a Fed “add on” to the amount offered to the public and doesn’t influence what the public pays a bit. So ignore it, put it totally out of your mind. Doesn’t matter in this context.

Hey wait a second John, you said in the intro that the bid-to-cover was overstated for this auction and for all current treasury auctions for that matter, aren’t you going to explain that before leaving the section titled “(Bid-To-Cover)”? Actually no, it comes later in the piece but explain it I will.

Where did the bids come in on 11/9?

Quick aside about what a competitive bid actually is. Its an amount at a certain yield. So if I had 100 million dollars that I wanted to potentially invest in this 30 yr bond being auctioned I could bid all 100 million at a bid level of 4.744% yield. If I had done so I would have “won”/take 100 million of the auction, though at a winning yield of 4.769% (since everyone gets the auction high yield). Alternatively, I could have bid 50 million at a bid level of 4.760 and 50 million at a (lower) bid level of 4.770%. If I had done that, I would “win”/take 50 million of the auction at the auction high yield of 4.769, but that’s it, the 50 million I bid at a bid level of 4.770 would not be accepted. I would “win” only 50 million of the treasuries at auction. Finally, if I had bid all $100 million at a bid level of 4.769 I would have won/taken only $17.97 million in Treasuries from the auction. Why $17.97 million? Because in order to get as close to awarding only $24 billion worth of Treasuries (with some allowance for rounding to the $100 dollar increments) as possible, Treasury can only partially fulfil the bids at the high yield. Treasury reports what that partial take % is in the Allotted at High figure from the competitive auction results.

What do the auction results tell us about how the competitive bids in this auction were distributed? Starting with the most basic, we know that at least $23,910,420,000 (24b less the non-competitive bids) worth of competitive bids came in at the yield level of 4.769 or lower. We know this because treasury allocates the winning bids starting with the lowest yield (highest price) bids and moving up the yields until it has allocated the full amount. As a notional example lets say that the lowest yield bid in the auction was a bid for $500,000,000 of the Treasuries at a yield level of 4.587. Treasury says, great, that bid gets accepted (running tally of $500,000,000). Now lets move up one bid increment to 4.588 and see if there are any bids at that bid level. Lets say that yep, there are two bids there, each for $200,000,000. Treasury says great, accept those bids (running tally $900,000,000). Now move up to the next bid increment 4.589. No bids at that yield level, so move up to the next bid increment 4.590, lets say there is one bid there for $300,000,000. Accept it (running tally $1,200,000,000). OK John we get the point, you going to do this through the next 179 bid levels (.001 increments) until we reach the auction stop at 4.769 when the running tally of accepted bids hits at least $23,910,402,900. No but treasury will as they allocate the auction to the winning bidders.

The Low Yield

Through bid level 4.590 we had accumulated $1,200,000,000 of winning bids which is ~5.02% of the total 23.9b competitive bids that were accepted. I did this deliberately because that means our Low Yield is 4.590. The Low Yield represents the yield level where at least 5% of accepted competitive bids were tendered. This corresponds to the actual Low Yield of 4.590 in the 11/9 30yr auction (as reported in the competitive auction results shown above). So while its super unlikely, my theoretical bids to illustrate how the treasury bid acceptance mechanics work could potentially exactly match reality, and we can be certain that ~$1.2b (or a little more) of bids were made at yield levels of 4.590 or lower.

Think about that for a second. 1.2b was bid for at a yield level 17bp below the high yield of the auction and 12.6bp below the “When Issued” (WI) yield of 4.716. Basically, whomever was bidding the 1.2b at those levels intended to win that allotment regardless of where the auction ultimately priced. As a practical matter, its almost completely price insensitive bid. So why wouldn’t those bidders just bid non-competitively then? Well, because Treasury caps non-competitive bids at 10m so if you want more than that, you have no choice but to bid competitively. “Competitively” but really not. Yeah but so what John, its just 1.2b of the 23.9b awarded. Fair, but it starts to draw what I think is an important point. There is a large volume of “competitive” bids in Treasury auctions that are mostly price-insensitive that much more resemble non-competitive bids where the goal is to get the volume of treasuries being bid on at a “reasonable” mkt yield/price, whatever the market (price-sensitive competitive bidders) decides.

To be clear, when I say price-insensitive I mean it strictly in an auction bidding sense. The root demand to invest in the Treasuries is of course sensitive to price and the end investor’s decision to “buy” those treasuries almost always takes the price range of similar duration treasuries into account, but once the decision to buy in some volume at that price range has been made, those “price-insensitive” buyers are looking to get the market price, not help set it. For example, your tennis buddy tells you “dude put your money in long term treasuries, they are a great deal right now” You say “I think you are right” and buy a chunk of some bond fund. You made a price sensitive decision to “buy bonds”. The bond funds AUM is now up and to meet their investment strategy they need to buy more of the newly issued 30 yr. When that bond fund makes that bid though, they really don’t care what the price is so long as it reflects market, they need the allotment they are bidding on to keep their portfolio in line with their advertised investment strategy. From a bidding sense, their bids are “price-insensitive”.

The Median Yield

Just how large is this mostly price-insensitive bid? Well we cannot know for exact sure, but the Median Yield (reported in the competitive auction results shown above) gives us an important clue. The Median Yield is similar to the Low Yield except that it represents the yield (at or below) where at least 50% of accepted competitive bids were tendered (and of course accepted). For the 11/9 30yr auction the Median Yield was 4.650. So for that auction ~12b of bids were at the 4.650 yield level or below. 11bp below where the auction priced and 6.6bp below the WI yield of 4.716.

Hold on John, whats this “When Issued” (WI) yield you speak of. Is it the “Yield the Treasury wants the auction to price at” like you tube bro told us? Uh no. The Treasury wants the auction to price at a yield of 4%, no make that 3%, hell why stop there make that 2%. Point being, the Treasury wants the auction to price as low yield as possible since that means the least expense to taxpayers. But its an auction and as a result its gonna price where it prices, so whatever the Treasury “wants” is irrelevant. What the WI yield actually is, is the yield at which the bond that’s about to be auctioned is trading the moment before the auction bids are due. Wait huh? How can the bond be trading before its auctioned, or for that matter issued. Well, its not literally the bond, rather it’s a contract to buy/deliver that specific bond when it does issue but the price the buyer will pay (yield) is established at time of trade, so before the auction. Pre-auction When Issued trading acts as a price discovery mechanism for the auction and projects a market (well at least those folks participating in the When Issued trading) expectation of what the auction will price at. Since many of the same folks who bid at auction are also participants/market makers in the WI market (e.g. the dealers) the WI yield immediately before the auction is usually very close to where the auction ends up pricing.

<Quick aside, Im glossing over a whole lot of interesting nuance in the WI market with my brief description of it above. For example, the on the run 30 yr bond turns over every 3 months (remember new issue Feb, May, Aug, Nov reopens in other months). The WI market allows funds who desire/need to be in the OTR security to transition to the new OTR before the old OTR stops being the OTR and offers an alternative vs. buying the new OTR at auction (or after). Thus, action in that market (aside from just the price/yield level right before the auction prints) could impact bidding behavior in the auction itself. If say a bunch of very price sensitive funds bought aggressively in WI making the liquidity providers in the WI market (e.g. dealers) net short going into the auction, it could lessen the auction bid volume from funds but increase the bid volume or raise the price of the bids from dealers to cover their WI delivery obligations. Unfortunately, I have no access to data in this market so I cant explore further.>

The WI yield level shortly before the auction is a known thing to all the bidders who are going to bid in the auction. So if you are a price-insensitive bidder who mostly just wants to get the amount of bonds you bid for at whatever the auction price ends up being, you pick a yield level some spread lower than that WI yield that you are comfortable is sufficiently below it (since the auction is likely to price near it) to ensure your bids get accepted. How big a spread should be sufficient?

Stop Throughs, Tails and the Bid Buckets

Another of the big traditional metrics of how “strong” an auction is just what the difference is between the WI Yield and the Yield at which the auction prices (aka High Yield). If the auction prices at a lower yield then the When Issued yield it is said to “stop through” by however many basis points (each bid increment level is .1 of a basis point) lower than the WI Yield it prices at. Conversely, if the yield the auction prices at is higher it is said to “tail” by however many basis points higher than the WI Yield it prices at (exactly is “on the screws”).

So If you are a price insensitive “competitive” bidder, it would make sense to look to the history of the largest stop throughs for the tenor and use that as your guide to how much lower than the WI Yield you bid in order to more or less guarantee you will get your full allotment. For the 30 year bond, four basis points is almost always sufficient. With that, I think it’s a good framework to put the bid levels into four broad buckets:

1. Price-Insensitive: Bids at yield levels 4bps (or greater) less then the WI yield. – Historically these bids have almost no chance of not being accepted so they are more or less completely price insensitive bids, the aim of these bids is to win their allotment. They definitely comprise considerably more than half the bids.

2. Price-Sensitive below WI: Bids at yield levels between WI yield and 4 bps below WI yield. – Sliding scale of price sensitivity. Bids 2.5-4bps below WI yield still very likely to be accepted, more uncertain as the bid yield level rises to the WI yield. These bidders (particularly less than 2.5bps)are basically saying that they want their allotment, but only so much and accept a realistic risk of not winning their allotment if their price cap (their bid yield level) gets exceeded. It is interesting to note that this group of price-sensitive bidders could buy pre-auction at a cheaper price (higher WI yield) than their bid (though not necessarily where the auction prices) but are choosing not to for some reason. Why don’t they? It’s a good question. If any readers have good answers, I would love to hear them in the comments.

3. Price Sensitive above WI: Bids at yield levels between WI yield and 4-5bps higher than WI yield – Fully price sensitive bids with a reasonable chance of still being accepted (at least for the bids 0-3bps higher than WI yield) starts transitioning to speculative/backstop bids as you move to 4-5bps above WI.

4. Backstop/Speculative: Bids higher than 4-5bps above WI yield – A mixture of backstop bids that primary dealers are required to submit and speculative bids by others with almost no chance of being accepted (except of course for the bids at 5-5.3bp above WI in the 11/9 auction, historically very unlikely to does not mean wont get accepted)

But who is bidding in these buckets?

The Bidders

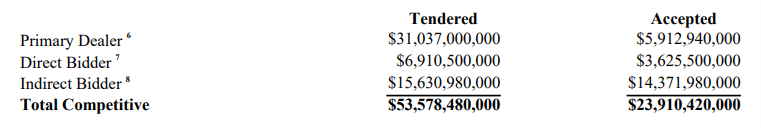

The competitive auction results that Treasury posts immediately after the auction break out the total and successful bid amounts by primary dealer, direct and indirect bidders. For the 11/9 30 yr auction it was as follows:

Those breakouts are useful but incomplete and there are some misperceptions about who constitutes those bidder types. The biggest misperception is that indirect bidders are just a proxy for foreign buyers. The reality is the portion of the indirect bid which is foreign varies significantly with the tenor and also auction to auction but almost never amounts to even half of the indirect bid, usually being much lower. For example, in the 11/9 30 year auction, Foreign and International investors were allotted 3.43b. So assuming all that was bid indirectly (which I don’t think it literally is, but for ease of analysis I treat it as if it is for the rest of this post and even if it isn’t all, its likely at least substantially most) the foreign bid was at most ~24% of the accepted indirect bid. Treating the indirect bid as just a proxy for foreign demand can lead to some faulty conclusions. If you compare the 11/9 30-year auction to the most recent prior auction of a new issue in August shown here.

(skipping the two more recent reopens because the offering amounts and auction dynamics are somewhat different) you see a ~2b drop in indirect bids made (17.6b in Aug, 15.6b in Nov) and ~1.2b drop in indirect bids accepted and you might conclude a significant drop in foreign demand

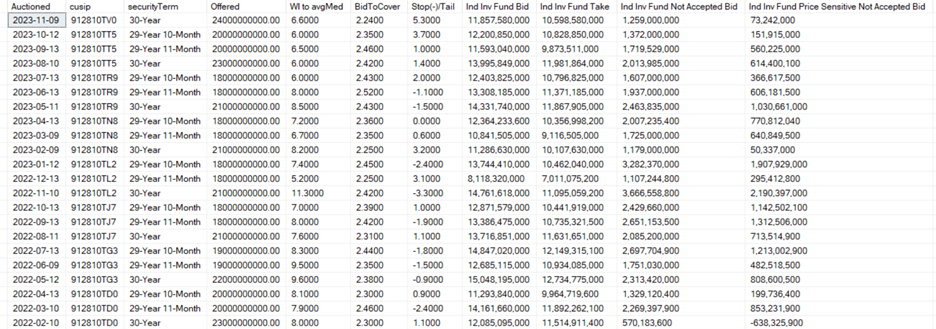

In fact, there was a drop in foreign allotment from the august auction to the November auction, but just 100m dollars from 3.53 to 3.43b. So who actually does constitute the vast majority of the indirect bid? Investment funds. And how do I know all this? Because Treasury tells me here https://home.treasury.gov/data/investor-class-auction-allotments

The challenge is they don’t release this data concurrent with the auction results, you have to wait until a week or so after issuance so its not available for snap analysis or auction grading. So grade if you wanna, but just know that a rise or fall in indirect accepted bid may or may not correspond to a similar rise/fall in foreign accepted bid.

For the 30 year bond though, the much bigger story is Investment funds.

How do the direct and indirect bidding categories actually break down then?

Directs – Mostly (~80-85%) investment funds (the ones that can bid directly at auction) though with a not insignificant chunk of non-primary dealers and brokers (e.g. primary dealers took 5.912b in the 11/9 30yr vs 6.422 that went to dealers/brokers so 510m or ~15% of the 3.625b Direct Bidder take must have gone to those non-primary dealers and brokers). Depositories, who would otherwise be in this category basically aren’t buying at all (at least directly at auction) in the 30 year recently. Its possible that a portion of the pension/retirement/insurance bid was also bid directly, but a super detailed look at the last couple years of auction data seems to indicate they bid indirectly. In any case, they take nothing many auctions and only occasionally have a chunky bid. That said, for the remainder of this piece I treat them as indirect bidders.

Indirects – Still mostly (~75%) investment funds (the ones that cannot/choose not to bid directly at auction) with the balance mostly being the foreign buyers but also including the occasional pension/retirement/indirect bid along with little bit of individual bid and for that matter “other” bid cause I got to put them somewhere.

What exactly constitutes investment funds? Treasury defines that too (here https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/276/investor-class-descriptions.pdf) : “Includes mutual funds, money market funds, hedge funds, money managers, and investment advisors”. Humble request to Treasury, breaking out the bids by those investment fund components would be super appreciated. Im sure they will get right on that for me.

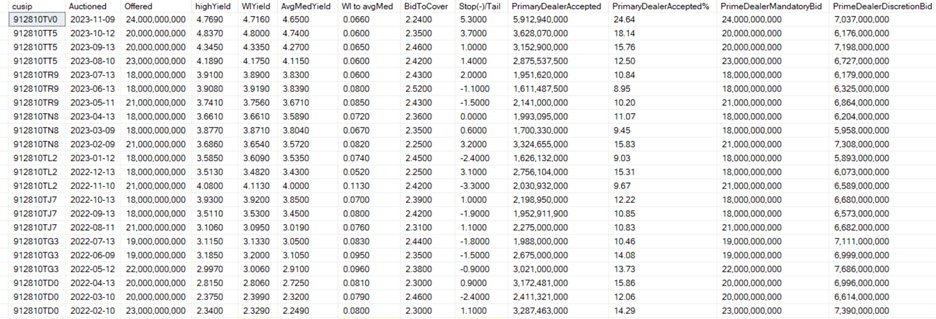

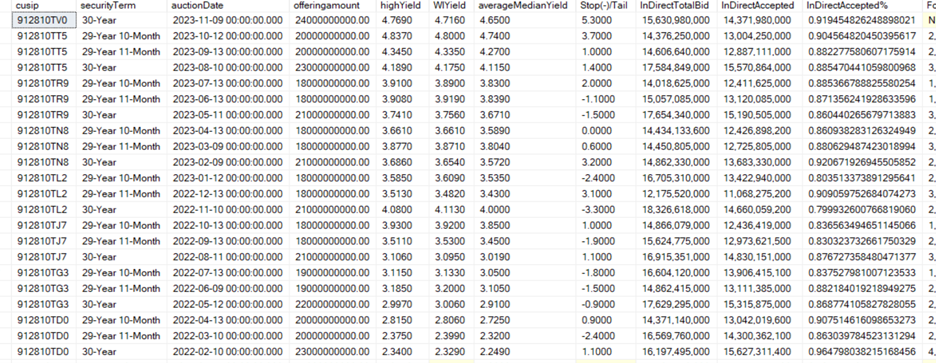

Who is bidding and in what amounts is interesting (even if our data is somewhat coarse) but even more interesting I think is in which of the four buckets the different bidders bid in or more specifically for each bidder type how much do they bid in each of the buckets. What John, you got access to Treasury’s detailed data on bids received? Nope, but analyzing the public data closely from the last 20 or so 30 yr auctions we can actually start to put together a pretty good picture (I specifically chose to stop the lookback when QE stopped, just seems like the QE buys would significantly alter auction bidding behavior and I didn’t even want to try to sort any of that out)

The general technique starts with combining the auction results (retrieved via Treasury API) with the investor class allotment data and stitching in the WI yield. That last bit was a super PITA for a sans terminal hobo like myself but stitch it I did (I could have approximated using the last minute pre-auction yield of the OTR which is data I can get but I wanted it exact so I mined Twitter instead). That combined dataset allows me to make some reasonable (I think) assumptions to determine the volume of bids per bidder type/investor class. From there, by observing the tendered vs. accepted for these bidder types over the 20 or so auctions I look back over, and in particular auctions with large tails or stops, patterns start to emerge about things like a baseline level of price insensitive bid for direct and indirect investment funds and where the price sensitive bids seem to reside. Its far from perfect, but there’s more signal there than youd think there might be. As always, Ill define my assumptions, show my work and you can decide for yourself.

Bid Price Sensitivity Profile

Primary Dealers

The primary dealers appear to place bids in 3 of the bid buckets. By far the largest amount of their bid goes into the Backtop/Speculative bid bucket (4-5 or more bps above WI). Why? Because it is their responsibility as primary dealers to do so. In the words of the Fed. (here https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/primarydealers)

“Primary dealers are trading counterparties of the New York Fed in its implementation of monetary policy. They are also expected to make markets for the New York Fed on behalf of its official accountholders as needed, and to bid on a pro-rata basis in all Treasury auctions at reasonably competitive prices.”

There will always be a bid from Primary dealers sufficient to buy the whole auction from Treasury, even if no one else showed up.

Primary dealers also seem to have a consistentish price-insensitive bid of somewhere around 10% of the auction offering amount. You can see this in the past auction data, particularly for auctions that have a large stop through. Why focus particularly on those? Because take the 11/10/22 auction which had a 3.3bp stop through. No bid at a yield level higher than 3.3bp below the WI was accepted, so almost by definition all the accepted bids in that auction were “price-insensitive”.

Finally primary dealers seem to also place a price sensitive bid between the WI yield and 4-5bp above it. Ive broken out in the table above the “discretionary” bid of the primary dealers. This is the total amount they tendered less the mandatory bid. That “discretionary” bid includes both the price-insensitive bid and the price-sensitive bid. Note how the amount (and %) accepted rises as the Tail on tailing auctions does. It seems that the vast majority of this price-sensitive bid is placed above WI with a concentration fairly far above it.

Applying this analysis to the 11/9 auction for Primary Dealers where 31b was bid with 5.9b accepted:

· 24b (none accepted) at some backstop bid level > 5.3bps above WI

· 1.1b (none accepted) of price sensitive/speculative bid > 5.3bps above WI

· 3.5b (all accepted) of price sensitive bid > WI but <= 5.3bps above WI (this chunk of bid is what actually priced the auction)

· 2.4b (all accepted) of price insensitive bid < 4bps below WI

Direct Bidders

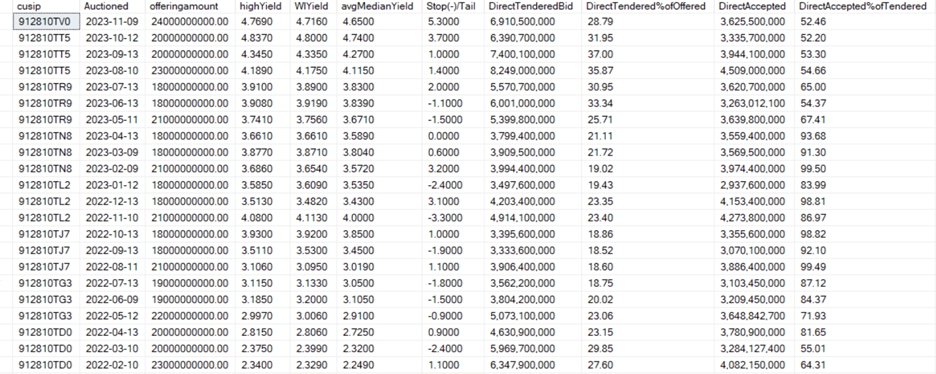

Prior to breaking down the volume and range of where each direct bidder bids, we have to resolve just what the hell is going on with the Direct Tendered bid. Starting with the May 2023 auction there seems to have arisen a large speculative bid (I mean, look at the 11/9 auction 3.3b of the direct bid was not accepted vs. 3.6b that was in an auction that tailed by 5.3bps, bids higher than 5.3b above WI historically have almost no chance of being accepted so wildly speculative), reversing a trend that had been in place since June of 2022 where the amount bid by direct bidders pretty closely matched what they took. But then prior to June 2022 the trend of a large speculative bid seemed to be fully in place starting in June of 2020 reversing the trend of very little speculative bid for a time before June 2020. I was initially baffled by this bidding behavior but there is a very simple explanation for it.

Its not a speculative bid at all. Its almost certainly non-primary dealers placing this bid to demonstrate to the NY Fed that they have the capability on a consistent basis to meet their pro rata share of treasury auction backstop bids. In order to become a primary dealer a dealer must:

ASL Capital Markets was added to the list of primary dealers on April 4, 2022. Notably, the direct tendered bid in the 4/13/22 auction dropped by 1.3b which is consistent with ASL leaving the ranks of direct bidders and joining the ranks of primary dealers. The rest of the “speculative” bid dropped off two months later. I assume there was another dealer “auditioning” to be a primary but dropped the idea before the June 9 2022 auction.

Explaining the recent non-primary dealers “auditioning” their capability to the Fed, my guess is the exit of Credit Suisse as a primary dealer in early summer prompted it. From the data it appears 1 started in May, another in July and a third in August. How can I tell?

Well take this month for example, knowing that the “auditioning” dealers have to demonstrate their ability to bid for its pro rata share “based on the number of primary dealers at time of the auction” we can surmise that there are likely 3 dealers “auditioning” to become primary currently. Why? Well there are presently 24 primary dealers, so each dealers pro rata share in the 11/9 auction was 1b. So if we take 3b “auditioning” dealer backstop bid out of the direct bid tendered we are left with 3.9b direct tendered and 3.6b direct accepted with an overhang of 300m, which honestly seemed a little high given the 5.3bp tail. For the auction the month earlier that overhang was worse, removing 2.5b (offered amount was 20b for that auction) from the 6.4b direct bid leaves us 3.9b bid vs 3.3 accepted or a 600m overhang on an auction with a 3.7bp tail. Compared to the 2/9 and 12/13/2022 auctions which had tails over 3bp and overhangs of only 20 and 50m, 600m is just way too high.

The resolution seems to be that although technically pro rata for 24 dealers would mean 1/24th. In practice, the primary dealers consistently bid around 130% of the offering amount. 10% of that for the allotment they need to win (their price-insensitive bid) and 20% which is likely laddered up (yield levels) from some point above WI until it reaches their backstop bid. Accounting for this “extra” bid for the dealers “auditioning” to the Fed brings the overhangs (adjusted for stop/tail) into much better alignment with how the direct bids looked in the year or so when no dealers were “auditioning” to become primary. With just one tiny problem, adding ((1.2 * number of auditioning dealers / 24) * the offering amount) to the other (non-primary) dealers take works nicely for the auctions from May through October but generates a negative overhang in November. Obviously that is literally impossible since the other direct bidders (almost soley the large investment funds) cant take more than they bid. So I adjusted the “extra” bid down to 9% to compensate. Playing with the numbers to make them work eh? John. Well yeah but I think its reasonable since only the pro rata bid should be strictly necessary, plus I think those 3 dealers preening as primary may well have been spooked by the October auctions 3.7bp tail and pared back their bids in the November auction to closer to what was strictly required. Applying these adjustments allocates the direct bid as follows:

As a final note on the subject, the excess tendered direct bid (starting in May) indicative of 3 non-primary dealers “auditioning” for the Fed isn’t just seen in the 30 yr. Rather, it is seen in all tenors. So its not just the 30yrs bid-to-covers that have been overstated with direct bid that is literally there but not at all indicative of actual demand, its every Treasury auction right now.

Non-Primary Dealers -

We know from the investor class allotment data that non-primary dealers took ~510m out of the 3.625b accepted direct bid in the 11/9 auction. We cant specifically know what portion of the 510m was due to price insensitive bid vs. price-sensitive bid but I think its likely most of it was price-insensitive. Why? Well if you compare the 12/13/2022 auction to the 1/12/2023 auction, the non-primary dealers took nearly identical amounts from auctions that offered the same amount yet one auction stopped through by 2.4bp and the other tailed by 3.1bp. If there was price sensitive bid there you wouldn’t expect the takes to be the same. Accordingly, I model the non-primary dealers take entirely as price-insensitive.

That leads to non-primary dealer bids in the following buckets:

· 3b (none accepted) at some backstop bid level > 5.3bps above WI

· 270m (9% of 3b backstop) (none accepted) of price sensitive/ bid > 5.3bps above WI

· 509m of accepted price insensitive bid < 4bps below WI

Direct Bidding Investment Funds

We can isolate the direct investment fund bid by subtracting the bid by non-primary dealers from the total direct tendered bid. Similarly, we calculate the direct investment fund take by subtracting the non-primary dealer take from the total awarded to direct bidders. Technically we should subtract the take from Depositories as well but the next auction Depositories take a significant amount of a 30yr auction (or hell take almost any amount) will be the first auction in quite a while that they have done so effectively they can be ignored for now.

Accordingly, the direct investment funds bids and takes for the last 20 or so auctions look like this.

With the notable exception of the last two months, for the past year, large investment funds seem to have had a price-insensitive bid of ~15% of the offered amount at auction and a price sensitive bid of ~3% that seems clustered close to or maybe a little below the WI yield. I establish the ~15% price sensitive bid using the 1/12/23 auction with its 2.4bp stop along with the 5/11 and 6/13 auctions with 1.1 and 1.5bp stops. Comparing the takes in those auctions with the takes in the 3/9 and 4/13 auctions, (on the screws and a slight .6bp tail) and then the 7/13 – 9/13 auctions with larger tails is what leads me to conclude there is a ~3% (of offered) price-sensitive bid. That bid seems to have shifted recently though from slightly lower than WI yield (3/9 through 6/13 auctions) to more above it (8/10 and 9/13 auctions). Respecting the more recent trends I assume the price-sensitive bid is now above WI.

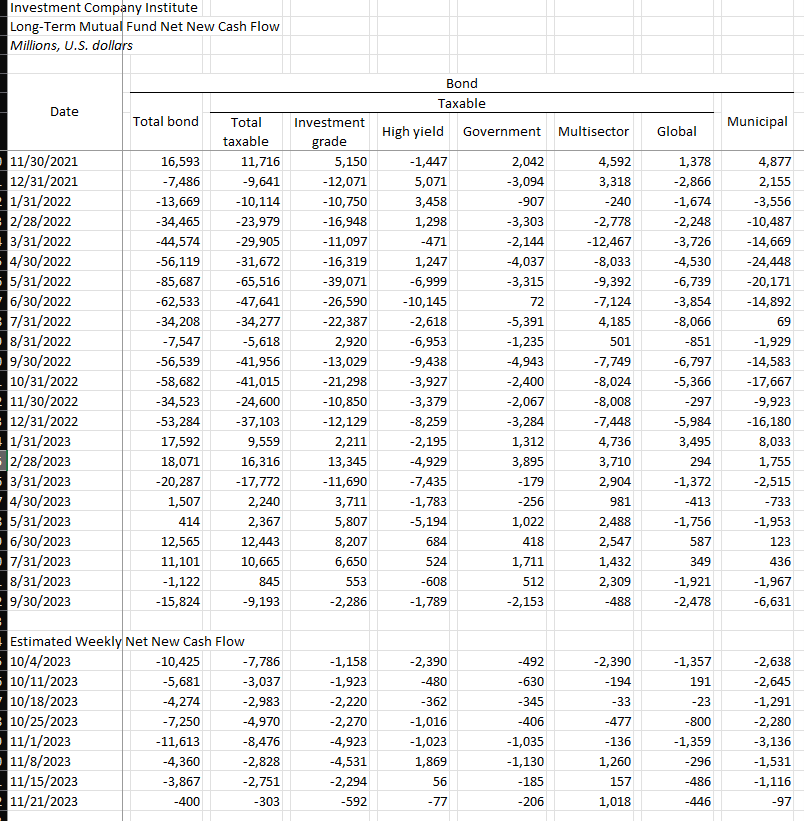

But…. The last two months have notably broken the trend, the ~15% of offered price-insensitive bid did not materialize in either auction. I think this is most likely explained by, the end user price-sensitive demand that drives the volume of price-insensitive large investment fund bid size fell in the months leading up to the previous two auctions. Less AUM in long term bond funds, means less price-insensitive bid from those funds in treasury auctions. There appears to be support for this idea in the ICI long term mutual fund net new cash flow data. Note how declines in government bond funds started in September (most of the lead up month to the 10/12 auction and accelerated into the two weeks before the 11/9 auction). Note as well how the aggressive declines in 2022 corresponded with a structurally lower price-insensitive bid from large investment funds in 2022.

Its coarse support and there are hiccups in the correlation (December and November 2022), but its interesting nonetheless. So what was the price-insensitive bid on 11/9? I think the sensible thing to do considering the trading models of some of the investment funds like hedge funds is to keep the expected price-sensitive bid steady at ~3% of offered and downward adjust the price-insensitive bid to 10% and check back in after next months auction.

Applying to the 11/9 auction:

· 720m (all accepted) of price sensitive bid > WI but <= 5.3bps above WI

· 2.4b (all accepted) of price insensitive bid < 4bps below WI

Indirect Bidders

Indirect bidders are mostly split between foreign buyers and investment funds with a tiny smidge of individuals and pension fund/retirement fund/life insurers mixed in.

Foreign + Individual Investors + Pension Funds/Retirement Funds/Life Insurers (PRLs)

Whoa John, that’s quite the bundle eh? Yeah but it simplifies the analysis and to be fair, the combined take of individuals and PRLs is small and I think the price sensitivity of the Individual and PRL bid is similar to the foreign bid. Specifically, I assume all this bid is largely price insensitive. If a foreign entity, individual, or PRL has decided to bid some amount at the auction they are likely bidding with the intent to win that allotment (a noncompetitive “competitive” bid). I doubt there are a lot of bids above WI where the foreign entity, individual, or PRL wants it at say 4.72 yield, but doesn’t at 4.70 yield. Considering how high the usual indirect acceptance rate (vs total indirect bid) is (typically 85-90%),

I think its safe to assume that almost all of the relatively small amount of price sensitive/speculative bid (that doesn’t get accepted) comes from Investment Funds.

That leads to Foreign/Individual/PRL bids in the following buckets:

· 3.77b of accepted price insensitive bid < 4bps below WI

Indirect Bidding Investment Funds.

In the 11/9 auction indirect bidding investment funds bid 11.85b total with 10.6b of it accepted. Considering that the auction tailed by 5.3bp that more or less means 1.25b of speculative bids. Looking over the recent auctions this is typical with speculative bids from indirect bidding investment funds usually running at about 10% of the total bid. Im at a loss to explain this bid (and there is no preening dealers explanation to cover this one) but its clearly there.

It also appears there is a price sensitive bid of ~15%. This is best demonstrated by looking at the 11/10/22 and 1/12/23 auctions which both had large stop throughs so little to no price-sensitive bid would have been accepted. The result is corroborated by how the Not Accepted Price Sensitive Bid grows from next to nothing for large tailing auctions to our full ~15% of tendered for large stop through auctions. This leaves us with a rule of thumb that typically ~75% of the indirect bidding investment fund bid is price insensitive, which for the 11/9 auction means about 8.9b of price-insensitive bid. Wait how are you figuring that John? Well for any given auction if the auction stops through by a large amount (say 2-3 bps) than very little of the “price sensitive bid” ends up accepted. Conversely, if an auction tails by a large amount than almost all of the “price sensitive bid” ends up accepted. The 11/9 auction is convenient because it had such a large tail so all of the “price sensitive bid” (bids at a yield level between 2-3bp below and 4-5bp above the WI yield) was accepted. That allows us to isolate the speculative bid which in the case of the 11/9 auction was about 1.2b (~10% of the indirect investment fund bid) for the indirect investment funds. If we assume that bid to be somewhat structural and look back at other auctions we can start to get some insight into where in the price sensitive range, the indirect investment funds price sensitive bid falls. For example, the 10/12 auction had an indirect investment fund bid of 12.2b of which 10.8 was accepted. If we assume a speculative bid of 1.2b than we had another 200m of bid that was not accepted in the 10/12 auction. We also had a somewhat lower stop. Am I certain that 200m in extra not accepted bid was between 3.7bp above and 5.3bp above WI? No, only Treasury really knows that. But when you look back over the recent past of 30 yr auctions and compare the Indirect Investment Fund Price Sensitive Bid that was not accepted (calculated as the (total indirect bid – a 10% speculative bid) – the total indirect accepted (note the foreign/individual/PRL take cancel out since I am assuming those bids are price insensitive and thus take = bid)) with the Stop/Tail of the auction you can see that there appears to be something like a 2b band (~15%) of price sensitive bid for the indirect investment funds. Also, by looking at the auctions with stops/tails near the WI we can get a sense of how much of the price-sensitive bid is above vs. below WI (looks like roughly a 1/3 above 2/3 below split)

Applying this analysis to the 11/9 auction for Indirect Bidding Investment Funds :

· 1.265b (none accepted) of price sensitive/speculative bid > 5.3bps above WI

· 560m (all accepted) of price sensitive bid > WI but <= 5.3bps above WI

· 1.12b (all accepted) of price sensitive bid < WI but > 4 bps below WI

· 8.9b (all accepted) of price insensitive bid < 4bps below WI

The full Bid Profile

So in sum it appears the bid breakdown in the 11/9 auction approximated something like this (ranging from high yield level to low yield level)

· > 5.3 bps above WI – 29.635b total backstop/speculative bids: 25.1b in Primary Dealers, 3.270b from Preening non-Primary Dealers and 1.265b from Indirect Bidding Investment Funds)

· WI to 5.3bps above WI – 4.78b total: 3.5b in Primary Dealer Price Sensitive bid, 720m from Direct Bidding Investment Funds and 560m from Indirect Bidding Investment Funds

· 3.5bps below WI to WI – 1.12b total: 1.12b from Indirect Bidding Investment Funds

· < 3.5bps below WI – 18.079b total: 2.4b in price insensitive primary dealer bids, 509m from other dealers and brokers, 2.5b from Direct Bidding Investment Funds, 3.77b Foreign/Individual/PRL, and 8.9b from indirect Bidding Investment Funds

Conclusion

Perhaps Treasury’s pullback on increases to 30yr issuance in the November QRA was a good idea. As ugly as the 2.24 bid-to-cover looks for the 11/9 30yr auction, the real bid-to-cover of 2.11 (excluding the 3.27b in preening backstop bid by dealers “auditioning” to become primary) looks even uglier. Had Treasury offered 26b on 11/9 as recommended in the August QRA vs. the 24b it actually did, the real bid-to-cover would have been 2.02, dangerously close to touching the backstop bid. While that would still be light years away from an auction “fail” it would probably be somewhat legit worthy of a “catastrophic” label.

Ironically (sorta), with the rally across the curve since the 11/9 auction, the market is in a different mindset and as of now Id bet the 12/12 reopen of the 30yr will be a “solid” if not “stellar” affair.

Regardless of how it turns out though, hopefully you are now armed with the analytical techniques to make sense of the auction results (when they truly arrive on 12/22 with the release of the investor class allotments results). Until then and as always…

Thanks for reading,

John

Great write up, thanks for sharing.